Names are important. How something is called changes one’s relationship to it. The rose and baby’s breath on my table, gifted by Shima, conjourn up multiple intermingling images — love, loyalty, innocence — which both coincide and digress from the actual plants I see before me. Should I call baby’s breath by its linnean name, Gypsophila, this word would surely recall others.

As a society we’re learning how important names are. That’s why there’s so much to say: the names of children killed in Gaza, the names of Indigenous children lost to Residential Schools, the many overlapping Indigenous place names where I live (Toronto, derived from the Mohawk name, Tkaronto, is also called Gichi Kiiwenging in Anishinaabemowin — I’m not sure why this name hasn’t become well known too), those of trans people who’ve decided to change their names despite often hostile conditions, the lists go on.

Names have been so fickle my whole life. The shape of my name sounded different on the tongues at school versus those at home. The name of my mother adapted with her place. The names of my grandfathers I barely knew. Names are important, and they do change our subjective relationships, but they don’t determine the inherent meaning of the named.

Wait, did I just contradict myself?

In a recent body of work, rāz dār am / رادارم , I used the multiple valences of my family name as a starting point to engage with ancestral design practice and poetic exploration. My last name, Razdar / رازدار , means secretkeeper in Persian (or does it mean that in English? What does the word do in naming? What does the name do in wording? Onto what ground does the name cling in the midst of translation?).

The name is a sign. It points and I follow.

I honestly didn’t think that I would be writing about رازدارم in this post. I was going to write about my hereto unsuccessful, though deeply satisfying, quest to find a new name for this Substack (more on this later). I’m a poet, so shouldn’t the name of my new newsletter-blog reflect the connotative openness of language that I so admire?

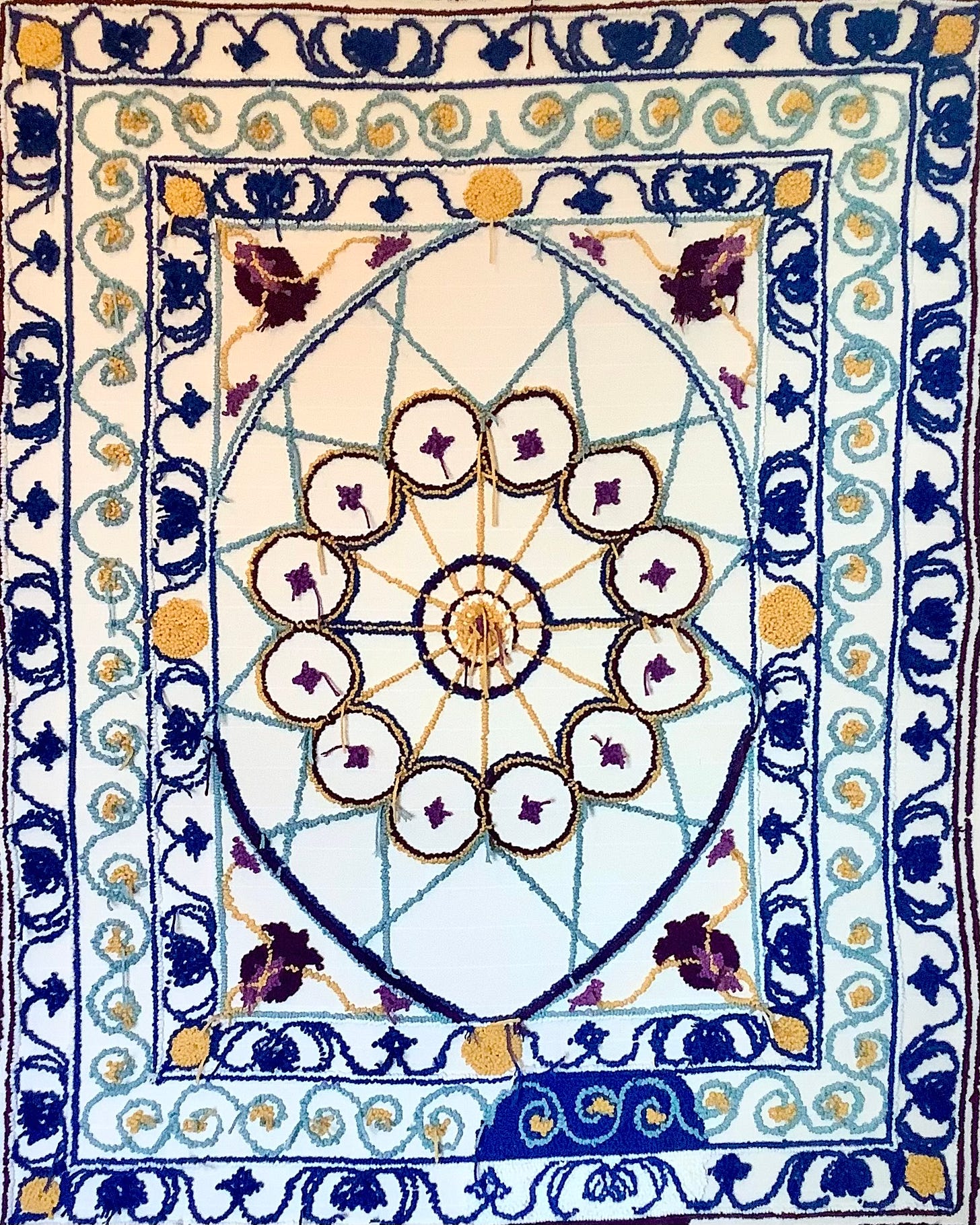

In any case, it’s coming on a year since I wrapped رازدارم . The end of its creation process came with the completion of this rug.

The body of work also includes a poem, zine, and poster (below). The poem zine and riso poster are available to buy on my website (click to follow the links!).

Since ending the project (is any project ever over?) last November, I haven’t actually shared it with the world. Not through social media. Rarely in conversation. Right now, the rug is tucked away in my studio (though I’m considering mounting it on my bedroom wall, if only Phoebe won’t tear it apart), and I’ve been bad at selling prints. After a year, I feel the time has come to share —

My inspiration for this body of work came during one of the most difficult few months of my life. I had just finished an academic program I loathed, left a housing co-op that crushed my dreams for cooperative living in this city, lost a few good friends, lost a new job, floundered in social isolation (very tricky for a gemini!), all while stuck in Toronto’s long cold winter. When everything I thought worked stopped working, I needed to try something new. That’s where رازدارم came in.

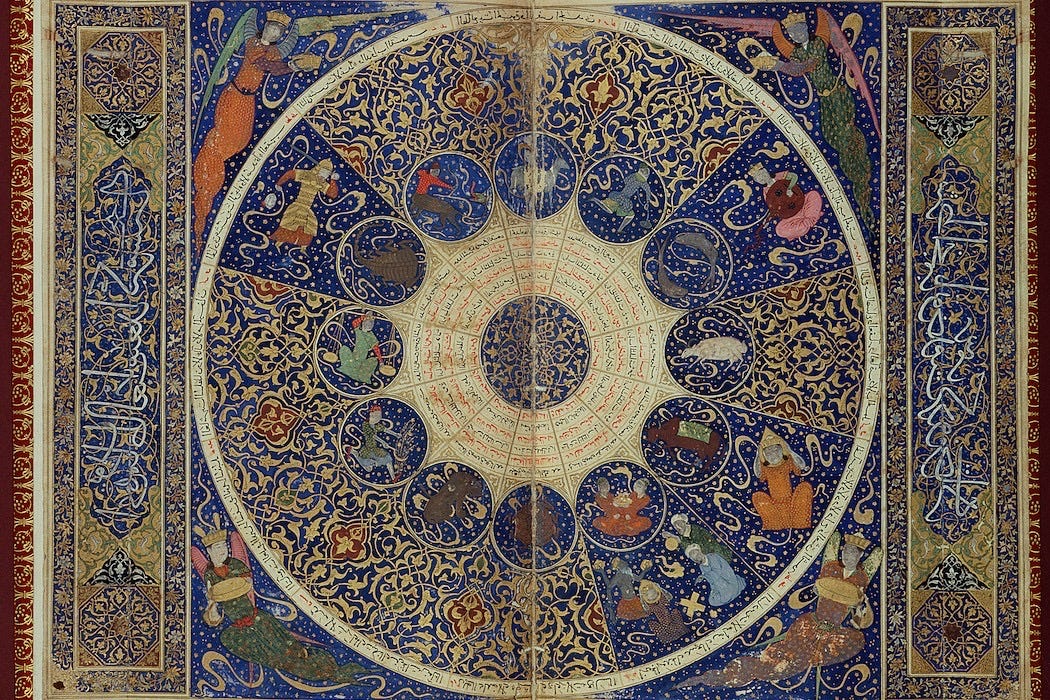

During (and absolutely due to) all of these trials and tribulations, I got way more into astrology. I learned about the houses, played with profections charts, and read about medevial Persian astrology. In my research, I came across this pretty well-known image — a birthchart horoscope for the 15th Century Timurid king Iskandar (who was a libra!) — with the twelve signs depicted by their traditional referents (libra as the scale, gemini as the twins, aquarius as the water bearer, etc.) among islamic and astrological scripture and richly detailed motifs. I was transfixed. It transfixed me.

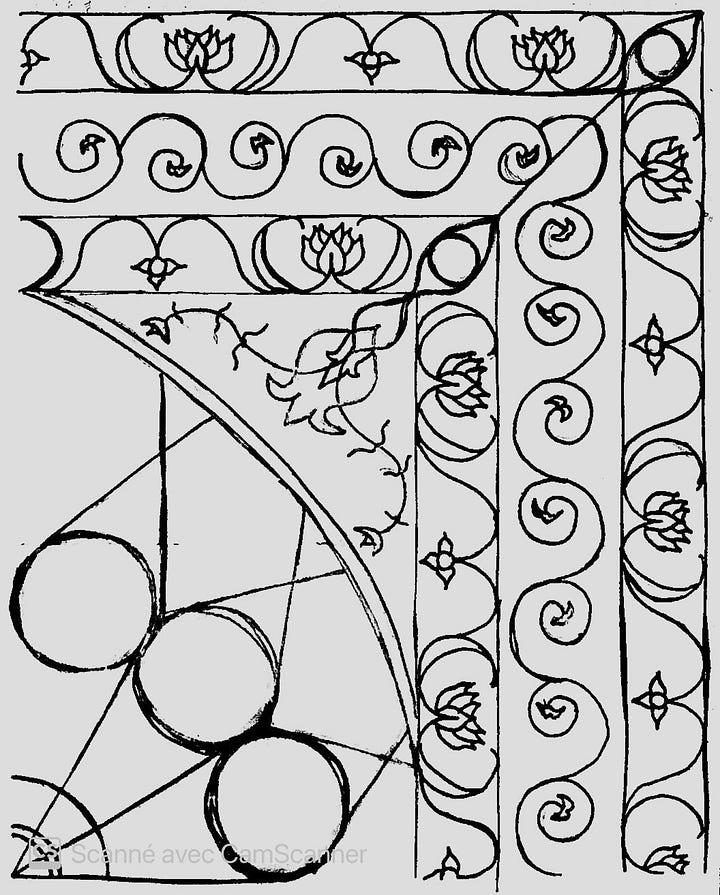

The spiral of time that saw me wading through all that hardship and delving into astrology also had me working closely with fibre and textile. Alongside shibori and natural dyeing, I was particularly drawn to traditional persianate rug motif — the symbols they are and the stories they tell together. The affective and even aesthetic resonance between my name, Iskandar’s birthcart, and the motif struck me. In February 2021, I got to sketching the first iterations of what would become a two year-long endeavor.

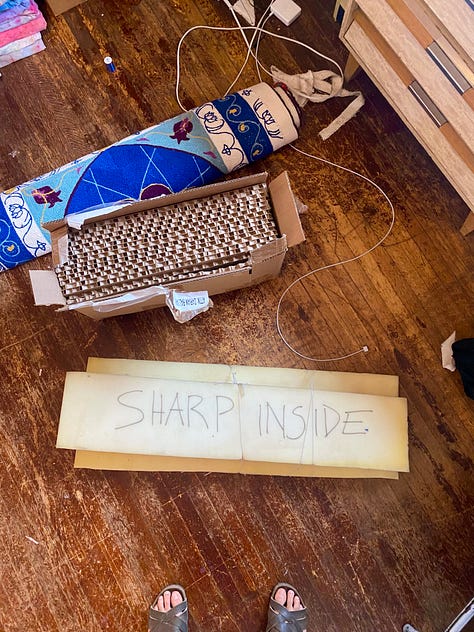

Early that Spring, I collected all the material I would need to make the rug: two Oxford punch needles, monk’s cloth to use as canvas, spruce two-by-fours to construct a four by six foot frame (I remember lugging those planks up the hill from the lumber yard to my old house… phewwww), and skines upon skines of wool yarn. I had very little idea what I was doing, but I had a vision and trusted that I would learn the rest (alas, the dreams of starting small escape me).

Over the next two years I worked on the rug in bursts. A month of intensive rugging followed by weeks of pause. The stop-and-go practice came from my need to find jobs, travel, do jobs, and rest. It resulted in a project that became the background of my life. In all the meetings I zoomed into, the mornings spent reading and stretching, and days writing and revising job applications — my secret was always there, waiting for the return of my attention.

As you see from this video, rug making takes time. Admittedly, I was a beginner, and in the long hours of punching yarn through loose cloth thousands of times, my mind often wondered how much more labor-intensive it is to rug in the traditional way (to which I quickly learned — A LOT — via websites like this).

In the hours I spent painting my motifs and patterns in woolen yarn, I jotted down words and phrases that came to mind (like secrets bubbling up from the source). Phrases like “Twelve months in one year pass” and “among my buoyant body / a revolution collects / in my orbit” ended up in a poem that exists alongside the tapestry in this body of work. This poem made its way into this pocket-sized fold-out zine.

I don’t know how many hours I put into this project. I don’t know how to count or call all I gave to it. What I do know is this: the rug, like me, holds many secrets, as much as it contains traces of the two years I spent pouring into it. I’m reminded of what my friend, former roommate, and fellow long-project person, Lizzy, told me halfway in, when I felt beat by how long it took to complete: all the time you give your art lives on in that art forever (this is not an exact quote . . . Lizzy, if you’re reading, help me out here!).

As much as part of me never thought I would finish the rug, part of me never wanted it to end. Maybe that’s why I’ve been so hesitant to share the news of its completion.

Almost a year later, the memory of seeing my rug become whole and feeling its smooth fibers cushion beneath the weight of my feet still feels so fresh.