Poetics of Place - Episode 2

"A Map is not the territory" and "Words are not the things they represent"

I want to think publicly about Poetics of Place. In my last post, I explained how I will be taking to Substack over the next eight weeks to share reflections from my workshop, Poetics of Place, which I am facilitating for a group of eight engaged learners online through Syracuse, NY’s Downtown Writers’ Center. I want to reflect openly on the experience of facilitating this workshop — its intentions, insights, and impacts — as to widen its reach and deepen my practice.

So, here we go into episode two on the week’s theme, exploring the workshop’s central idea, Poetics of Place . . .

January 30 2025 - Session 2: Poetics of Place

The term “poetics of place” is vague for a reason — it allows for a variety of creative practices (poieses) to gather under a common conceptual umbrella. Poetics of Place is the idea that place changes us and that we change place, but it’s also more than that.

When I say “Poetics of Place” I am referring to the loops and cycles of transformations (often so slight we don’t notice, and sometimes so great that we can’t ignore them) that every being and every thing in a specific place is always engaged in. I change you as you change me, while the sound of crickets and dusk’s fading light changes us, and, with our changed conditions, we change the place we inhabit. There’s absolutely an unseen energy to it, but it’s also material. We go about physically shaping the world in our movements, interactions, and creations.

There is multi-dimensional and multi-directional relationality everywhere. And every place invokes all other places so that where I am sitting writing this on my laptop in my apartment in Mexico City is tied to the street outside as much as to wherever you are reading this and where you will be next. This is a kind of relationality we may call “social ecology.”

The difficult task is creating work that accepts the messy, unclassifiable nature of these relationships. In the Occidental-European cartographic tradition since the Renaissance and until the present day, maps have been used as a tool to make the many entangled social ecologies on Earth less complex. I’m thinking specifically of the idea that maps are realistic and true. Like the many movements of realism in art history, especially in painting and photography, we can trace the idea that maps honestly portray the real essence of a place (or that they should, at least, aspire to) all the way back to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle.

In our last workshop session, I introduced Aristotle’s theory of essentialism. In few words, Aristotle believed that words, and the ideas and things they refer to, point toward an essence. Think of this essence as an unchanging identity — as, for example, the word “apple” (English) refers perfectly to the apple tree’s fruit and the mind’s idea of the apple. If the word refers perfectly to its object, then that means one could translate the word “apple” from English to the word “manzana” in Spanish, “pomme” in French, or “سیب” in Persian without losing anything in the process.

While this there doesn’t seem to be much problem with the translation of apple, we start seeing the cracks in Aristotle’s theory with more nuanced ideas like happiness, excitement, or despair — words pointing to subjective experiences. Perhaps the perfect philosophical foil to Aristotlean essentialism are the thousand nuances between Spanish’s ser and estar and their incomplete translation as “to be” (English), “être” (French), or “بودن” (Persian).

Even more doubtful Aristotle’s essentialism appears should we start to think in terms of geography. Earth (word), earth (concept), and earth (living rock in space): Aristotle would say that they all point to the same essence that is Earth. More over, he would say that representations of Earth, such as maps, must capture its essence — that is, they must be true, accurate, and real — and that it is possible to do or be so.

Let’s think about this for a moment. . . What is the Earth, really, and how do maps represent them?

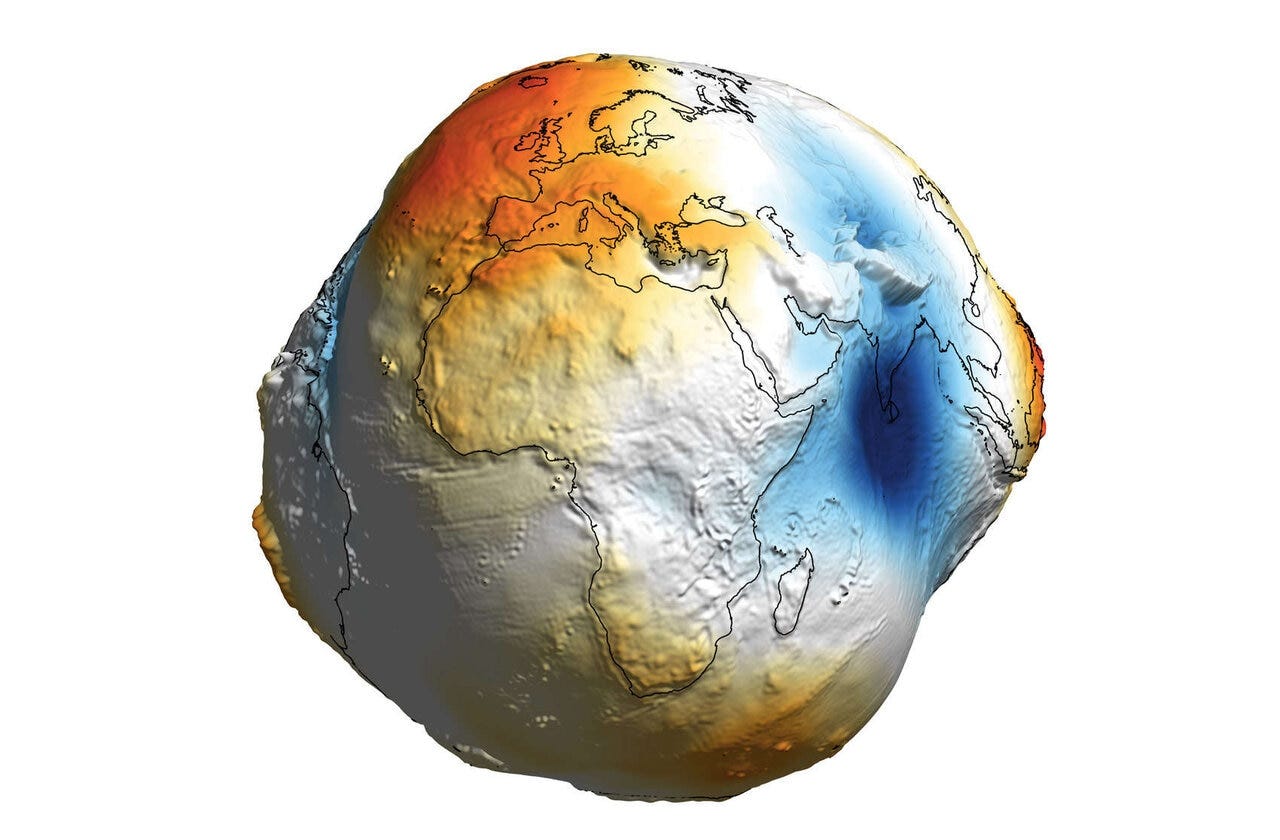

In session we looked at the Geoid — a lumpy model of Earth based on measurements of gravity’s uneven pull on the planet’s surface. While we often imagine the Earth as a uniform sphere, contemporary science tells us that an uneven distribution of mass across the globe gives it a lumpy shape. This means that sea level in Colombo, for instance, is 300 metres lower than sea level in Manila. Chew on that for a moment.

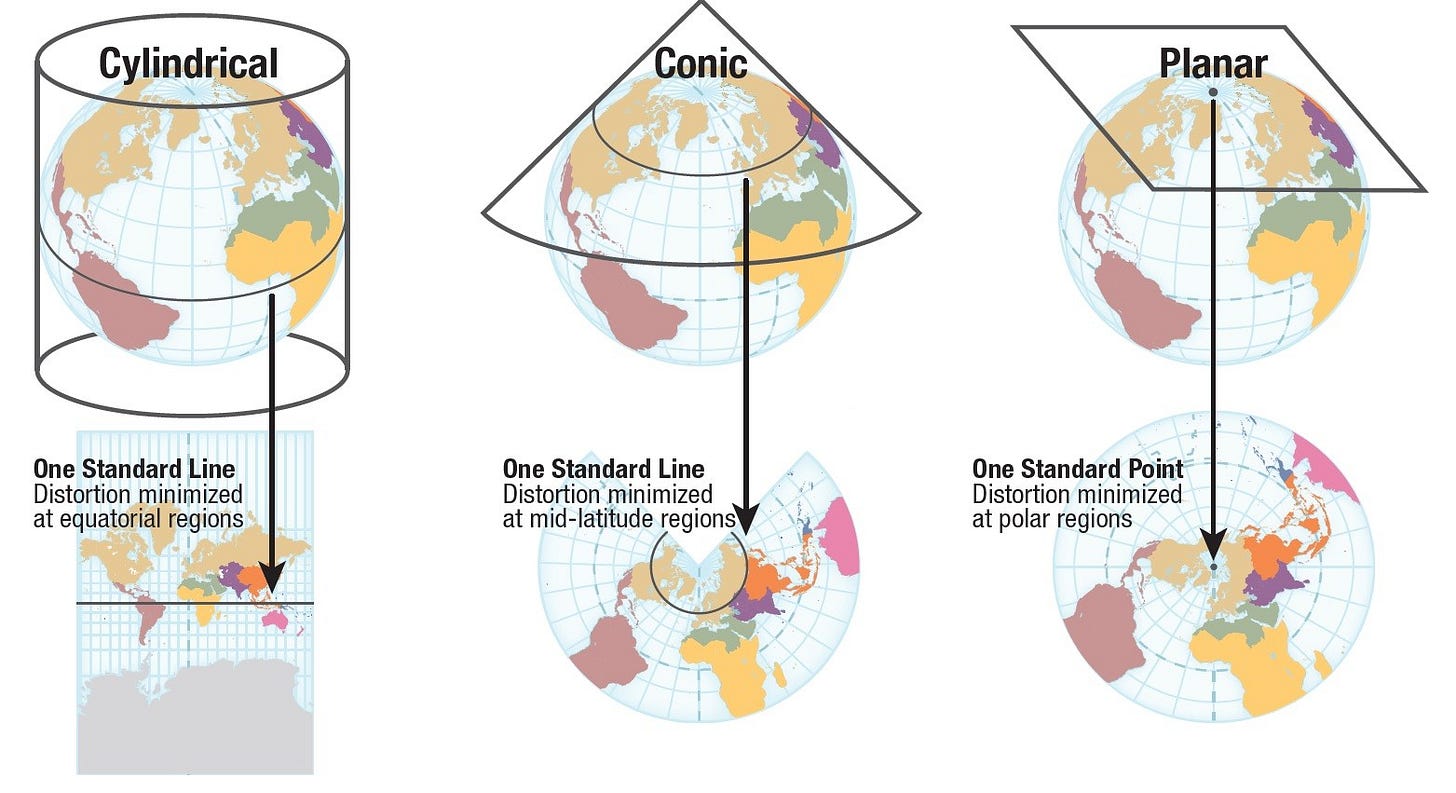

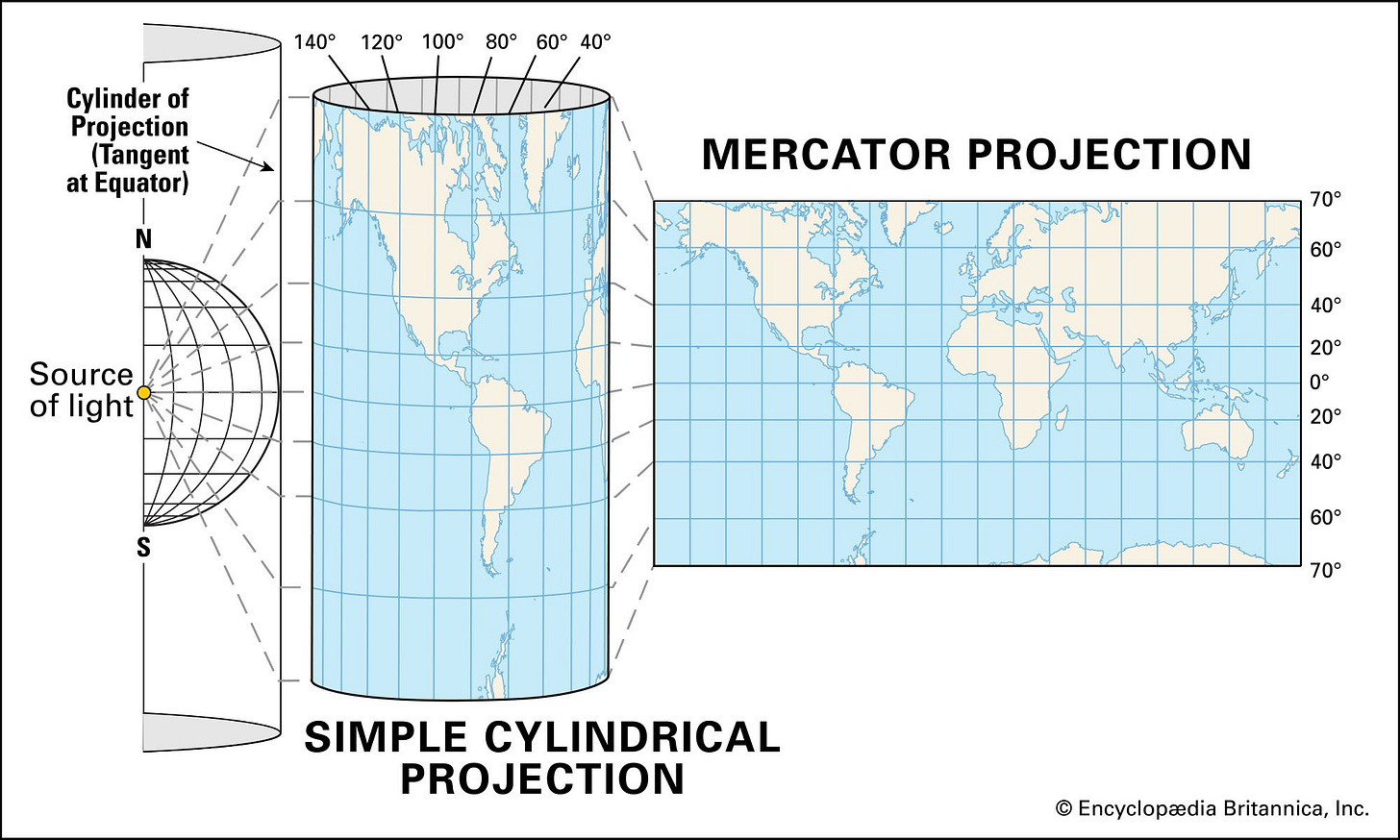

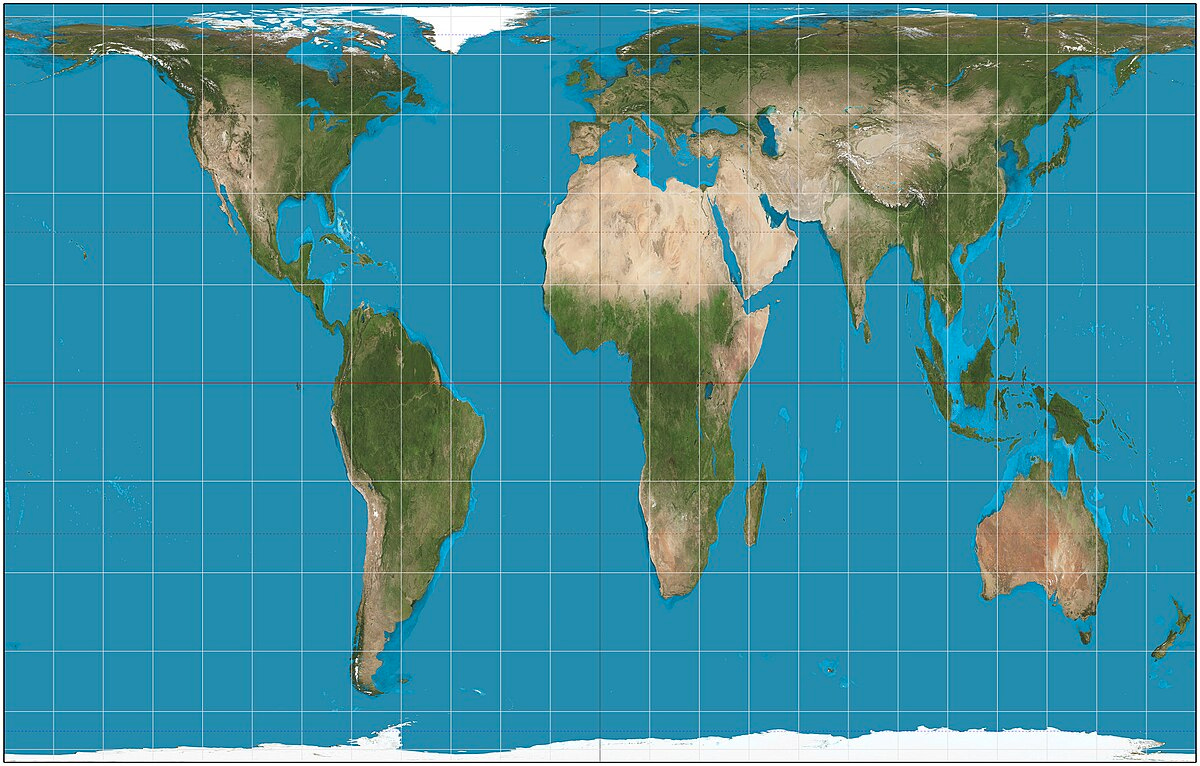

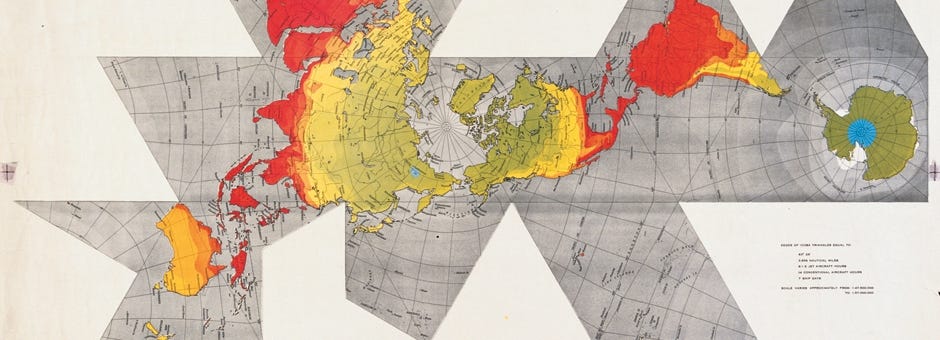

I like to say that modern cartography is about making the Geoid make sense — taking the Earth, which is basically unimaginable and useless, and making it an image that is useful. Modern cartography relies on projection systems — mathematical techniques that interpolate the earth’s supposedly spherical surface into flat images, such as in the below diagram. Crucially, all projection systems require a level of distortion. That is: it is impossible to represent Earth without moving away from the real.

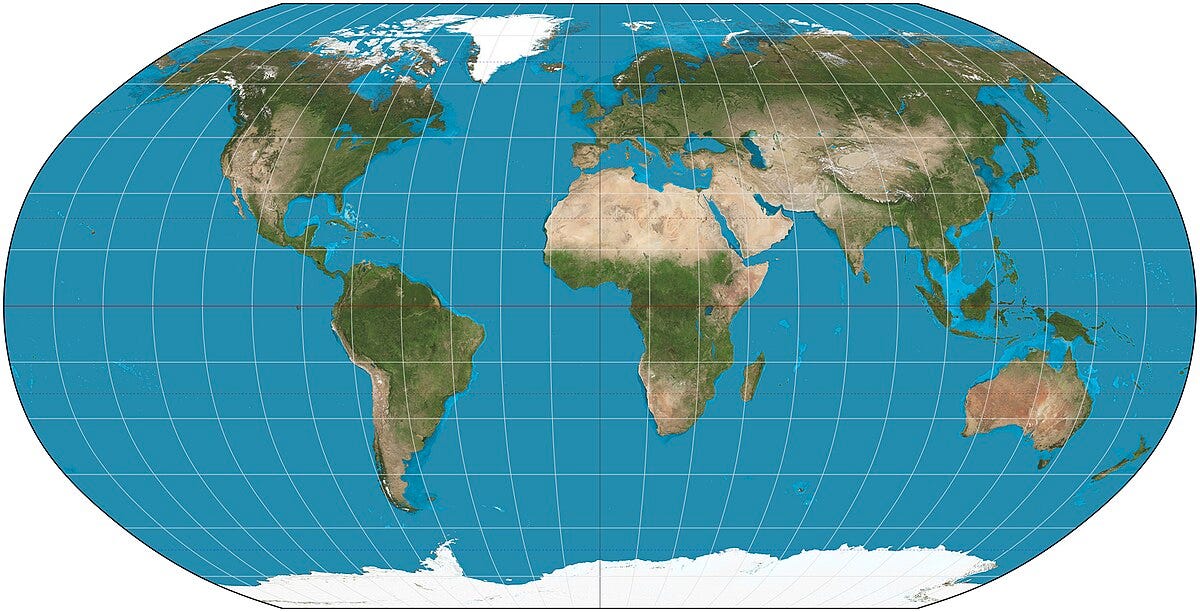

One implication of the impossibility of cartographic realism is that projection systems become political tools — such as in the Mercator system, which bloats the image closer to the poles, making Europe and North American appear larger than Africa and South America despite the the fact that landmasses are larger closer to the equator. The Mercator is still today’s dominant projection system, used in Google Maps and Open Street Maps, though many alternatives are available such as the Robinson, Gall-Peters, and Dymaxion projection systems.

The mathematician Alfred Korzybski perfectly summed up this problem with representation in his statement “A map is not the territory.” In the below article, Korzybski uses the map as an example of the limits of Aristotle’s essentialism to evidence the limits of representation, and thus the limits of physical and mathematical models based in static positions. It’s not surprising that later on in the article, he writes “Words are not the things they represent.” Words and maps fail at doing what we we were taught they do, which is to tell the truth. Funnily enough, a mathematician had to come alone to remind us this.

It’s inside the failure of representation where a Poetics of Place thrives. In the context of a the impossibility of realism, we are free to represent the world as we please, knowing that nothing is real but everything is important. A Poetics of Place uses images, words, sounds, and materials not to say look, here is the truth of the world!, rather, it says: here is a way the world might be, and asks, What other ways might be possible?

Workshop participants expressed a range of reactions to this sequence of ideas: from excitation of encountering a novel perspective, to unease with the theoretical nature, and a general sense of curiosity about how this all relates to their everyday lives and writing practice. Sometimes I get ahead of myself with theory and forget about the practice, though I do find this conceptual foundation to be an invaluable tool in attempting unconventional kinds of place representations (weird maps), which is the goal of this workshop.

I wonder how they will digest this information and, in following weeks, accept the difficult task of stepping out of our usual frameworks and onto new, shaky territory.

In the third session, we’ll be working with Jane Rendell, critical geographer and architectural historian, and her idea “site-writing.” I’ll dig more into site-writing in the next post, but for now I’ll note that session 3 will involve a lot less theory and more practice — writing places with all the tools and talents at our disposal.

Wow, the geoid... idk I'm parsing the emotions of seeing that / shifting that image. Uff