In my last post reflecting on my 8-part Poetics of Place workshop, I discussed the Situationists’ practice of “deturning” (détournement), which is a way of using creative moves to satirize what they referred to as the “society of the spectacle.” In preparing that workshop and writing that reflection, I had a clear recognition: in learning and study, abstract ideas must be accompanied by concrete examples.

As a gemini sun, scorpio rising person, I love all things abstract. I literally wrote a poem with this name, which you can find in the UKAI Projects collection, Poetics of Synthetic Language. Notwithstanding, I’ve realized through the course of facilitating this iteration of Poetics of Place that ideas are only as good as what they the manifest. That is, what we do is just important as what we think.

Participants have consistently and fairly reminded me this. In early sessions, I focused heavily on the theory behind Poetics of Place, and the feedback I received was that the content felt rather untethered, opaque, or abstract. And, well, I did developed this research-workshop project through a theoretical re-evaluation of the counter-mapping workshops I facilitated from 2017 to 2022. So much of the conception of Poetics of Place was abstract that I forget how much doing, making, and lived experience played into its creation often without my conscious awareness.

By offering my participants a theoretical introduction to each week’s thematic idea accompanied by a concrete artistic example of its use, I am finding that things are starting to proverbially ‘click.’

Last week’s workshop, number six of eight, we focused on the idea of Poetics of Relation as proposed by Edouard Glissant. Developed throughout a lifetime of scholarship and poetry, Poetics of Relation is Glissant’s intervention into the theory of (post-) colonialism. He argues against rooting people, especially (formerly) colonized people, in stuck identities, which he says sustains dominating relationships between cultures.

Instead of insisting on fixed identities rooted in opposition with the Other, Glissant looked around him in the Caribbean and saw how mixed everything and everyone was. This mixing, or “Creolization,” is an example of the entanglement between different people and cultures, which Glissant sees as a defining feature of the modern. We can think of Poetics of Relation, then, as the idea that I make myself as you and a 10,000 others make me with me, or that I make you alongside 10,000 making you with you, and on, and on, and on. . .

Specifically, in the workshop we payed attention to the interludes that Glissant wrote in the book Poetics of Relation : reflections that appear throughout the book before the start of each chapter. These interludes include “Imaginary,” “Repetitions,” “Creolizations,” and “Generalization.” Here’s the first, for example:

What a way to open your magnum opus. Whether you’re already acquainted with Glissant or this is your first time reading his writing, you can immediately note that Glissant was also a fan of all things abstract. His writing (even in the original French) is known for its opacity: an acceptance of the unknown and incomprehensible, which he defended fiercely.

Despite this, Glissant recognizes that thought never occurs in a vacuum (“dimensionless place”) removed from context, but always in the messy terrain of the world in which we live. For Glissant, the myriad literatures, arts, and cultures of the world are the primary text through which Poetics of Relations is realized. Glissant reminds us that even the imaginary stands firmly on the moving terrain of the world.

What Glissant’s Poetics of Relation teaches me in this moment is that doing and thinking cannot exist alone. They are not mutually exclusive — they flow back and forth and mix together, get entangled, and cannot be pulled apart. Without each other there would be no doing nor thinking.

The work beholden (2019) by Rita Wong and Fred Wah, which follows the path of the Columbia River from headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to its mouth where it means the Pacific Ocean, is a perfect example of Poetics of Relation. Each parts poem and map, beholden is a multi-vocal meditation on what the River means. Each writer wrote their own poem, which snakes its way along with a collaged map of the Columbia, relating the many stories flowing through this watershed on the way: Indigenous, botanical, salmon, settler, hydro electric, and restorative.

I had assigned beholden to read before the sixth session, and I had volunteers read excerpts allowed for the class. This was a moment when things began to click — the theoretical ideas of Poetics of Relation began to make sense on a tangible, relatable level. The world of this poem and this map became an entry point for participants to explore the abstract concepts we studied with Glissant. At last, a vivid example of what it is to write with one hand on direct lived experience in the world and the other on the ideas animating one’s way through it.

On that note, I offer you more examples I gave my participants in last week’s presentation alongside the ideas from Poetics of Relation they relate to:

Errantry — the life and work of Frantz Fanon who, despite and perhaps because of his Martiniquais origin (like Glissant) found himself dedicated to the struggle of Algerian independence. See my post on “Errant Study” from December 2024 for further discussion on the errant.

Repetition — “If I Told Him, A Complete Portrait of Picasso” by Gertrude Stein (with audio of the author’s reading!)

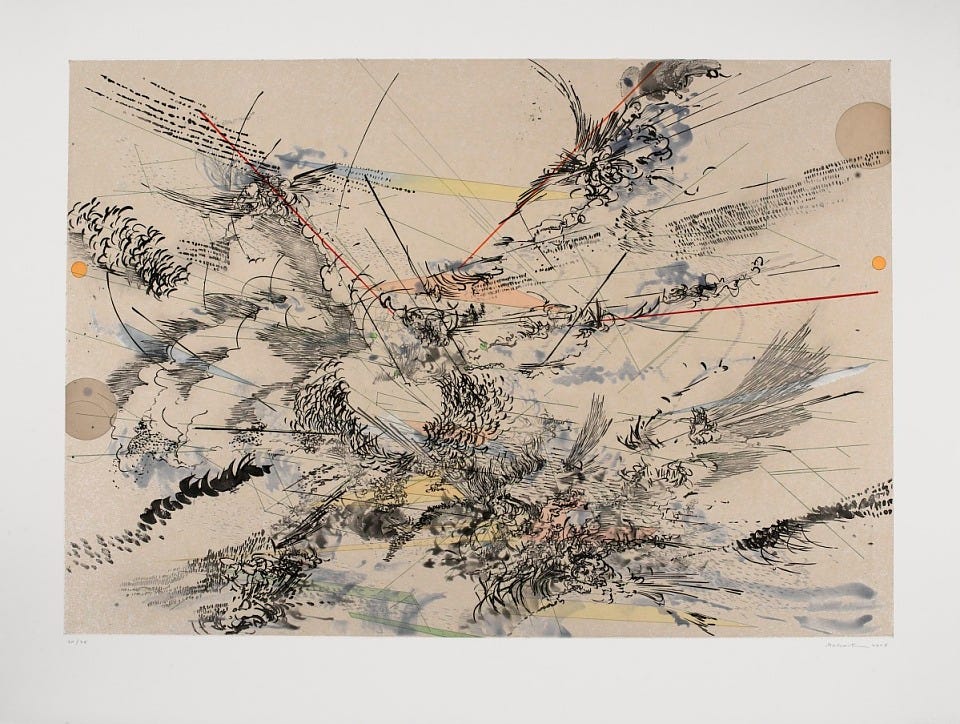

Creolization — “Atopolis: For Edouard Glissant” by Jack Whitten & “Local Calm” by Julie Mehretu

Opacity — photograms by Danielle Goshay and “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” by Wallace Stevens

This week’s session we’re expanding the field of relation into the more-than-human realm with the idea of Sympoiesis as developed by the one and only, Donna Haraway. Stay tuned for next week’s dispatch & read all about it!